Recently, a British Medical Journal (BMJ) study found that female doctors had a 76 percent higher suicide risk, compared to the general public. The study authors evaluated results from observational studies over a 64-year period across 20 countries. A 2021 study also showed that nurses, particularly female nurses, have a higher rate of suicide than the general population.

These results are concerning but not surprising. In April 2020, Lorna Breen, MD, an emergency medicine physician, died by suicide amidst the stressors of the pandemic. Although the pandemic has slowed, providers are still suffering. More recently, William West, MD, an ophthalmology resident in Washington, DC, died by suicide. In one of his final notes, he wrote “Imperfection is not allowed. Weakness is not either. When it’s there, its treated with disdain instead of an opportunity for learning and growth.”

In 2022, Congress passed the Dr. Lorna Breen Health Care Provider Protection Act, a first-of-its-kind legislative effort to address burnout and its effects on health workers. While the Dr. Lorna Breen Act has yet to be funded, Congress provided $120 million in the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 to address health and public safety worker mental health and resilience.

As a result, the Health Resources and Services Administration awarded 44 grants and one technical assistance center award, the latter of which was named the Workplace Change Collaborative (WCC). The WCC is a partnership of the George Washington University’s Fitzhugh Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (a quality improvement think tank and consulting organization), Moral Injury in Healthcare (a nongovernmental advocacy organization), and AFT Healthcare (a labor union).

While suicide is an outcome highlighted in the BMJ study, there is a deep-rooted problem affecting the mental health of all health care providers, regardless of gender, and it’s largely driven by burnout and moral injury. Addressing the issues underlying burnout and moral injury is essential to improving the well-being of health workers, and the WCC has worked with this in mind.

Burnout Versus Moral Injury

Most research related to health worker well-being has focused on burnout, “a psychological syndrome emerging as a prolonged response to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job.” Surveys suggest high rates of burnout; up to 60 percent of health workers experience it. Burnout in health workers is associated with alcohol abuse and dependence, depression, and suicide, as well as low job satisfaction, career choice regret, and intent to leave one’s job and the profession entirely.

Moral injury is a related but distinct experience that includes two aspects: first, a sense of betrayal by a legitimate authority in a high-stakes situation, and second, the transgression of deeply held moral beliefs and expectations. Following the perception of betrayal, if a worker can speak up and successfully address the moral difficulty, then transgression—and thus the process of moral injury—can be interrupted. For health workers, moral challenges often relate to compromised professional ethics because they cannot act in the patient’s best interest. The immediate responses to moral injury are shame, guilt, anger, and frustration.

Research on moral injury in health care is just beginning, but several studies suggest the importance of differentiating it from burnout. Moral injury may be the missing piece explaining why burnout continues to grow. One important study showed an estimated 0.57 correlation in prevalence across the two concepts, revealing that while some people experience one individually, many experience both simultaneously. Another study found that moral injury has an independent effect on intent to leave a job and exacerbates burnout.

While research about the distinctions between moral injury and burnout are still emerging, practical differences between them can be seen in the health care work environment. For instance, inadequate staffing—whether of nurses, physicians, or support staff—is a common scenario that elucidates the different types of health worker distress. When health workers must manage excessive workloads with inadequate support, they experience the job demand-resource mismatch that frequently results in burnout. When a nurse is regularly assigned to care for 20 patients per shift, or a physician routinely has 40 (or more) patients scheduled for each clinic day, the level of work is physically and emotionally exhausting. Each professional likely comes away from those days feeling ineffective because they could not assess patients adequately, administer medications on time, or sufficiently explain diagnoses and treatment plans. Finally, they may begin to “numb out” or depersonalize to tolerate that level of stress. But adequate staffing or time away from work might be sufficient to resolve those feelings.

However, if repeated requests for additional staff fall on deaf ears, those professionals may feel betrayed by the hospital administration whose resource decisions force them to lower their standards of care, effectively transgressing their professional oaths. Continuing to work under such conditions may lead them to question their health system’s moral framework and, subsequently, their own morality—wondering if they are still the good nurse or doctor (or social worker, physical therapist, and so forth) they vowed they would be—for working there.

Health workers may experience either burnout or moral injury as an isolated challenge. However, early work indicates they frequently co-occur. Therefore, where one is frequent, the other must be investigated.

The WCC’s National Framework

The WCC developed a national framework for Addressing Burnout and Moral Injury in the Health and Public Safety Workforce, building upon recent reports from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; the US Surgeon General; the Department of Veterans Affairs; and others.

Environmental Factors Related To Burnout And Moral Injury

Our framework recognizes the factors outside health care and public safety organizations (environmental factors) that create the conditions that drive burnout and moral injury. These include societal norms, such as structural racism and other power differentials; systems-level policies and regulations, such as reimbursement structures and credentialing criteria, technologies and market forces; organizational-level factors, such as internal rules, the existence or absence of measurement of worker well-being, and leadership styles and accountability for burnout and moral injury; and lastly, work and learning environments, which are at the heart of the problem, in which individuals ultimately experience the effects of the multilevel factors.

Drivers Of Burnout And Moral Injury

The lived experiences of these factors are denoted in the framework as drivers, expanding on and updating the original organizational areas of burnout identified by Michael Leiter and Christina Maslach. We differentiate the drivers that are key to the problem of relational breakdown from those that are more related to operational breakdown. This distinction is not mutually exclusive; the relational and operational problems certainly coexist and interact to affect lived experiences. However, organizational leaders are more willing to discuss and modify operational drivers than relational ones. Moreover, relational drivers occur most acutely when there is a conflict with the sacred oath of doing no harm—that is, when organizational decisions conflict with patients’ needs and wishes, health workers are left having to speak or act on behalf of the organization rather than the patient.

The first and perhaps more important relational driver is distrust, which may occur between workers and management, within teams, or between patients and frontline health workers. Other relational drivers include values conflict, lack of control over the practice environment, and inequities, such as unfair treatment and discrimination, which can particularly affect women health care workers.

Some of the important drivers on the operational side are lack of safety, excessive demands, and inefficiencies, such as administrative burdens, chaotic workflows, and poor communication.

All of these drivers are filtered through individual moderating factors, which is why some people experience burnout or moral injury while others don’t, even when they’re exposed to the same environmental factors and proximal drivers. These moderating factors may partly explain gender and other disparities in mental health outcomes, including suicide.

The Process And Outcomes Of Burnout And Moral Injury

These drivers can result in either burnout or moral injury. The myriad of outcomes of burnout and moral injury manifest at the worker, patient, employer, and societal levels, but they are not experienced equitably, as the recent findings on gender disparities in physician suicide rates may suggest.

Strategies To Address The Crisis

Traditionally, strategies to promote worker well-being have focused on the individual level or on operational issues, which are both important and absolutely necessary. Especially for health workers experiencing mental health crises, access to employer-sponsored, evidence-based services and supports is critical. Yet, to address the factors that trigger a domino effect of burnout, moral distress, and resulting harms, our framework clarifies the need to address organizational and larger system-level issues.

Addressing relational breakdown is foundational to this process. One striking example is that while increased nurse-to-patient staffing ratios improve the quality of care, staffing alone is insufficient. Specifically, nurse practice environments, including team dynamics and the relationship with management, must also improve to see the benefits of improved staffing ratios on nurse satisfaction. In other words, more resources cannot alone solve the problem of relational drivers.

Implications For Action

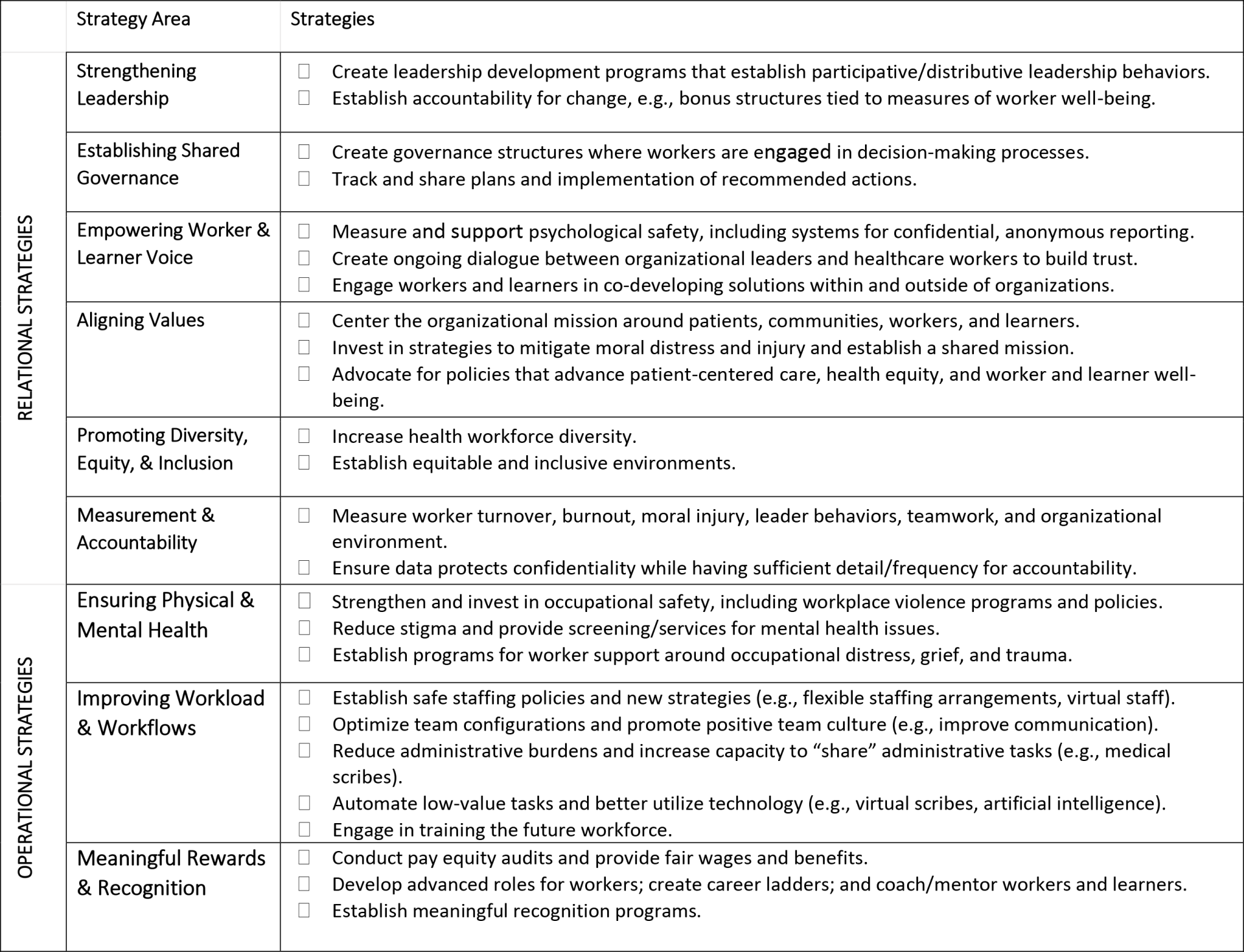

Consistent with the emerging body of work on trust led by Mark Linzer and colleagues, the primary implication of our framework is that more work needs to be done to address moral injury and rebuild trust. To build trust, frontline health workers must have a greater voice in the patient care process. This may require major changes in organizational operations, leadership styles, and accountability (exhibit 1), as well as government and private association policies and programs; the aim must be to establish evidence-based practices, support change through grants or technical assistance, protect workers and learners (health care students and trainees), and hold organizations accountable.

Exhibit 1: Strategies to address burnout and moral injury in the health and public safety workforce in health organizations

Source: Workforce Change Collaborative. Addressing burnout and moral injury. Washington (DC): George Washington University; [cited 2025 May 5].

Leadership And Governance

Organizations must elevate frontline workers’ voices by establishing mechanisms for input into unit-level and organizational-level governance, regardless of whether workers are unionized. Leadership development, support, and accountability will also be needed to advance and maintain distributed/shared governance structures.

Aligning Values And Advancing Diversity, Equity, And Inclusion

In organizations where trust has been lost, early work must focus on intentionally acknowledging and addressing moral injury and establishing a culture of shared commitment that centers the organizational mission around patients, communities, workers, and learners. Actions in the operational areas will ultimately be needed to demonstrate commitment. Organizations can also advocate for policies that advance patient-centered care, health equity, and worker and learner well-being as a demonstration of commitment.

Measurement And Accountability

A first step is to systematically measure moral injury, burnout, turnover, and trust at an organizational level and to hold leadership accountable for these outcomes. Ideally, a summary measure of worker well-being should be developed, including burnout and moral injury. A standardized measure would allow all parties to track progress and hold organizations accountable. A dashboard that tracks these measures could be made available to all employees. Boards of trustees could hold CEOs responsible for these measures in annual performance reviews, perhaps by benchmarking against similar organizations.

Policy And Regulatory Incentives

Accreditors and state and federal governments could incentivize or require organizational changes in numerous ways. So far, value-based payment approaches led by Medicare have been insufficient to halt the rise of burnout and have since been discontinued, but higher payment for certain measures could change that. Developing new measures relating to worker well-being and turnover would alter the incentives for organizations. It could be included in public reporting, such as the Medicare Care Compare sites for hospitals and nursing homes. Private regulators can also advance policies to improve worker and learner well-being.

State and federal policy makers can also advance legislative mandates to address the operational areas of burnout and moral injury. For example, Oregon just became the second state to mandate nurse-to-patient ratios, and 18 more states are debating whether nurse staffing committees or mandates are the best route to stemming the exodus of nurses from hospitals.

Interprofessional Advocacy

Lastly, health professionals have historically advocated for organizational changes at each other’s expense. Even labor unions in health care are often organized separately by profession. Certainly, some interests vary across specific licensee groups, but health workers experiencing moral injury due to the broken health care system they work in share fundamental interests: improving working conditions, making the system more accessible and affordable, and improving patient safety and quality. Regardless of the profession or occupation, health workers’ actions to effect organizational change are weaker when they work against each other. Across unions and professional organizations, it may be time to consider harmonizing demands concerning moral injury and burnout.

Conclusion

Our framework highlights the importance of addressing burnout and moral injury. Early research in health care and other fields suggests that organizational leaders, policy makers, and researchers must acknowledge the relational and operational breakdowns in health care to address these issues to prevent more severe outcomes, such as those highlighted in the BMJ article. Although burnout has dominated discussions of health care worker well-being, continuing to focus on burnout alone will stifle progress going forward. Including moral injury—both as a way to describe what health care workers are experiencing and to inform necessary changes to workers’ environments—will move us closer to a day when stories of health care worker suicide are a thing of the past.

Authors’ Note

This work is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling $5,940,548 with zero percentage financed with non-governmental sources. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the US government.